COVID-19 has bluntly shown all of us that African-Canadian front-line essential workers have been disproportionally affected with this highly contagious and deadly virus, even without supporting comprehensive scientific data. We now know that visible minority researchers throughout Canada have been demanding the collection of race-based and socio-economic data for years, because it is required to determine future public policy and, specifically, now for the containment of COVID-19.

And throughout North America, as we now sit in the shadow of another serious wave in which thousands more people will likely die, we have no more time to waste before collecting the requisite demographic race-based data, and then formulating public policies that will build more socio-economic equity into Canada’s health-care system and thereby save precious lives. Many enlightened political leaders—from the governor of New York state, to the premier of Ontario—are now demanding that accurate scientific race-based data be collected and analyzed.

We’ve all changed. No more handshaking. No more hugs of sympathy and condolence. We must now observe a two-metre social distancing. And we’ve likely spent more time at home either alone or with family than any other times in our lives. And that, too, was something very different. When our economies reopen, what will it look like and what must be done to treat all citizens fairly?

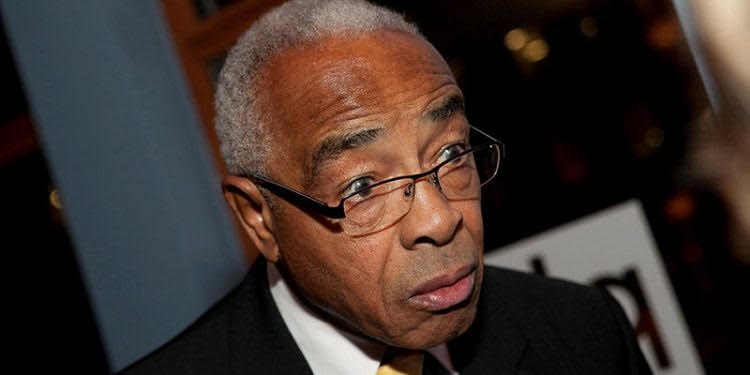

The inquiry could be headed by eminent Black jurist, Justice Michael Tulloch of the Ontario Court of Appeal, top left, and eminent African Canadian Candace Thomas. It could include other eminent Canadians, like Rona Ambrose, top right, Jean Charest, above left, and John Manley, writes Don Oliver. The Hill Times photographs and courtesy University of Toronto and LinkedIn

Our new, somewhat challenging, reality is the result of the sudden eruption and spread of COVID-19, and so we are now facing one of the most contagious and deadly viruses our modern society has ever met. Thousands have died and, sadly, it will be months before the carnage subsides in Canada.

This is a new coronavirus, and very little is known about it and its behaviour. But we do know for certain that it is lethal and that there is no known cure. Leading medical experts around the world willingly admit they are learning on the job each week as they observe things, like the COVID-19 massive inflammation in certain patients’ lungs that even the best ventilators cannot manage. But the good news is that thousands of Canadians who have tested positive are now fully recovered.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, pictured May 7, 2020, at his daily media availability at Rideau Cottage in Ottawa. Don Oliver is suggesting the prime minister set up a special commission this June, under the Inquiries Act, to study the various systemic problems in Canada that make African Canadians more vulnerable to COVID-19. The Hill Times photograph by Andrew Meade

The pandemic has raised many fundamental, but painful questions for me and I trust for all our governments, provincial and federal. These questions include: have all Canadians had equal access to our health-care system to fight COVID-19? Is social equity in short supply? Have the poor and the homeless had equal access to hospitalization, treatment, and cures? Are any Canadians being sidelined because of issues of gender, geography or race?

I try to keep current with the efforts our excellent scientific researchers and medical teams. There were times over the last three months that I felt sadness and anger when each day I read of the gross injustices and intrinsic unfairness in the treatment of three distinct groups of Canadians: our seniors, including some with special health needs in nursing homes and long-term care facilities where the death rate is totally unacceptable; people of colour or African-Canadians, particularly front-line essential workers and the poor and disabled; and other front-line health-care workers, doctors, nurses, orderlies, janitors.

Our seniors are entitled to the same medical treatment and care and social equity as other Canadians, notwithstanding their age and pre-existing medical conditions. The other two groups are putting their lives on the line for us every day and, regretfully, thousands of them across Canada are testing positive to the virus, and don’t even have the fundamental protective equipment for doing the job properly. I’m referring to basic gowns, gloves, face masks, shields, and sanitizers, all known as PPEs.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not over yet, but in this period of post-pandemic planning all levels of government must pick up the reins and help design, develop, and implement some forward-looking, creative public policies that will ensure these gross injustices will stop, and cease to exist. These public policies must go to the root of the problems that seniors face, and embrace substantial, fundamental change even to the structure, architecture, and internal layout of long-term nursing facilities that can accommodate concepts such as social-distancing.

I am delighted to see that many groups in the three levels of government in Canada have already made very extensive systemic changes into their long-term planning for the protection of the front-line health-care workers, by warehousing excess masks, gowns, gloves, etc.

But stockpiling PPEs is only part of the solution for African-Canadians and visible minorities on the front lines. Reliable Canadian race-based data and statistics are hard to come by, but our Canadian circumstances are akin to our American brothers and sisters. We share long-standing health and socio-economic disparities that make us highly vulnerable to pandemics like COVID-19.

Consider this. One-third of the people who have died from the coronavirus in the United States so far have been African American, and they only represent 14 per cent of the U.S. population today. When I began writing this piece, there were 2,900 deaths in Michigan, just to the south of our border. Some 40 per cent of those deaths were African-American even though they represented only 14 per cent of the population. And in St. Louis, 21 deaths and 64 per cent of those COVID-19 deaths were African-Americans. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s report on race-based data that was just released specifically pointed out a wide racial disparity: 83 per cent of patients with COVID-19 in hospitals it studied in Georgia were African American. In the U.S., the so-called front line is disproportionately Black and Latino.

In Canada, it is likewise disproportionate Black and visible minority, particularly for our front-line essential workers. I’m not just referring to cleaners and janitors inside a hospital. I refer to front line: public transportation workers in buses, trains, subways; building and cleaning services, garbage collection, grocery and convenience store workers, courier services, postal services, food delivery services, etc.; areas where so many of our Blacks and visible minorities are such a significant part of the workforce, and that, during the pandemic has been starved of essential PPE’s. The best contemporary example is the visible minority, essential, front-line workers in Cargill plants in Alberta. The infection rate and deaths are astounding.

Why is it that African Canadians suffer long-standing health and socio-economic disparity? What are the three levels of government planning to do about it? Well, I have seen little, if any, government interest or initiative to make the systemic changes required to interrupt the structural racism that confronts our Black front-line workers. Where were their masks, gloves, and other protective gear required for their employment? Where are the rules and government regulations that make it mandatory that African-Canadians can participate in the social equity that is part of the Canadian mosaic?

As I said earlier, community and national groups have been lobbying governments for years about the need for some demographic race-based data that could now include questions on the number of deaths; the number of hospitalizations; the number of those testing positive for COVID-19; and data to demonstrate African-Canadians disproportional medical access challenges.

OmiSoore Dryden, the James R. Johnston Chair in Black Studies at Dalhousie University. Photograph courtesy Dalhousie University

OmiSoore Dryden, the James R. Johnston Chair in Black Studies at Dalhousie University, was quoted recently by the CBC to have said, referring to the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, that: “they specifically mentioned that during this pandemic we need to respond to the lack of representation in high-level decision-making specific health risks among Black communities, racial discrimination and implicit bias that may pervade and continue to pervade in pandemic policy-making.”

In a recent, powerful op-ed by Paul Deegan and Kevin Lynch, headlined “A Roadmap for Canada after the Pandemic,” they recommended inter alia the federal government set up committee of respected commissioners across the political spectrum under the Inquiries Act, to investigate, in a comprehensive way, five special heads, including taxation and the economy, but nothing specific to the systemic racial problems facing African Canadians. I recommend that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau establish, this June, a committee under the Inquiries Act to study the various systemic problems in Canada that make African Canadians more vulnerable to COVID-19.

The inquiry could be headed by eminent Black jurist, Justice Michael Tulloch of the Ontario Court of Appeal. It could include other eminent Canadians, like Rona Ambrose, Jean Charest and John Manley, in addition to an equal number of eminent African Canadians and visible minorities, including Candace Thomas and Sharon Ross. Their preliminary report must be provided to the government no later than Jan. 31, 2021. The research division of the inquiry commission must include the finest researchers available in Canada. This inquiry is my personal vision for how we can eventually prevent so many innocent African Canadians from dying in such staggeringly high numbers from this and other contagious diseases.

Prime Minister Trudeau should also immediately establish a new government Department of Diversity headed by an eminently qualified African Canadian to oversee and implement the various recommendations of the above commission and others that may report. This pandemic will be with us for some time, so we must act now to save more lives.